Simple machines are basic tools, usually without moving parts, that make it easier to do work. Levers and fulcrums, the most basic simple machine, date back thousands of years. A claw hammer is a good example of a lever and fulcrum. When using the claw to extract a nail, the head of the hammer acts as a fulcrum and the handle acts as the

To extract the nail without a hammer, you could try to grip it between your fingers and pull up with all your might. But the force required to pull that nail even an inch will likely be more than you can muster. The hammer allows you to change the direction that you apply your might, pushing forward instead of pulling up. It also allows you to apply less force over a greater distance to move the nail that one inch.

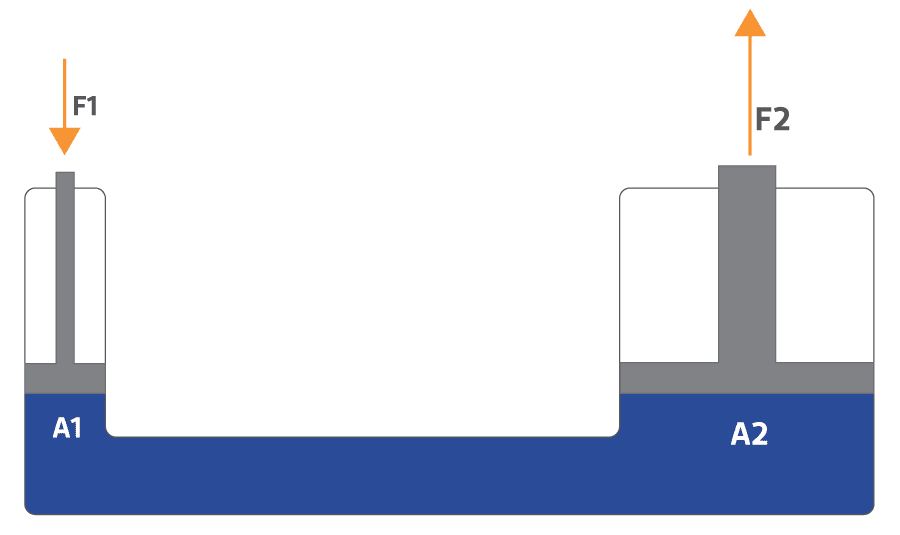

This is where the mechanical advantage of a lever and fulcrum comes from. Imagine gripping a nail with a hammer’s claw and resting the hammer’s head against the wall to use it as a fulcrum. The closer the fulcrum is to the nail, the farther you’ll have to move the handle to extract the nail.

As an example, let’s say that moving the nail 1 inch requires moving the handle 10 inches. Since you’re moving the handle 10x farther than the nail, you only need to apply 1/10th of the force

Lever and fulcurm

Cranes use this same basic principle to help them move heavy loads. Their long arms (booms) act as levers. The center pin of the crane is the fulcrum, like the head of the hammer. The load being lifted is the resistance force, like the nail. And the engine provides the effort force, like you pushing the handle of the hammer.

The length of the boom never changes, but the crane operator adjusts its angle to lift, lower, and move the load. Because the load (resistance force) is farther from the center pin (fulcrum) than the engine (effort force), cranes must apply more force over a shorter distance to move the load.

How Crane Counterweights Work

For big lifts, counterweights that weigh several hundred tons are attached to the base of the crane to prevent it from tipping over during lifts. The load is farther from the center pin than the counterweights. So to keep the crane upright, the counterweights need to be heavier than the load itself.

Counterweights actually need to be transported to the job site on trucks of their own. It would be impossible for a mobile crane to move with all that weight. Plus, building the crane on-site gives variability to how much counterweight is added to complete the project efficiently.

The weight of the crane itself also serves as a counterweight. So for smaller lifts, the crane may not need any supplemental weights. However, this is only true for small truck cranes that do not have an additional counterweight. Hydraulic all-terrain cranes travel with at least one load of counterweight by default.

Whether or not a lift requires additional counterweights, outriggers help to reduce the weight needed to keep the crane upright by distributing it over a greater distance. Outriggers are legs that extend from the base of the crane, lifting it off its wheels for added stability.

The boom isn’t the only lever on a crane. When a lift requires a farther reach than the boom can provide on its own, operators can attach a jib to the end of the boom. There are two fundamentally different types of jibs: boom extensions and luffing jibs.

On some cranes, the jib is always attached to the crane. These are known as swing away jibs. On other models, a second crane lifts the jib into place so that it can be pinned to the boom of the primary crane. When used for this purpose, the second crane is referred to as an assist crane. It’s not a unique design, just a smaller crane that happens to be lifting a jib on that day.

Once in place, boom extensions extend directly out from the boom. Luffing jibs, on the other hand, can adjust their angle mid-lift. You can see a luffing jib extending out from the boom of a mobile crane in the picture above.

The cables above and behind the jib are guy lines, which are used to change the angle of the luffer. And extending off the back of the boom is the mega wing, which provides support to keep the jib steady.

When the crane operator adjusts the angle of the jib, the far end of the jib moves a much greater distance than the point nearest the boom. The crane moves the jib by applying force to the end nearest the boom. Thus, it must apply a greater force over a shorter distance.

Booms and jibs are the best examples of how a crane uses levers to work. But if you’re as smart as we expect you are, you’ve probably already noticed that cranes are more complex than hammers. Right you are! Cranes are complex machines, meaning they combine multiple simple machines into a single device.

Pulleys/Sheaves

Cranes also work by using pulleys. The simplest pulleys are nothing more than a wheel held in place (fixed) with a rope looped over it. If you want to lift a load up, you can attach one end of the rope to the load and pull down on the other end of the rope. Rather than providing a mechanical advantage, fixed pulleys change the direction of your lifting force.

When the wheel of a pulley can rotate, it’s referred to as a moveable pulley or a sheave. These do provide a mechanical advantage. Unlike fixed pulleys which are attached to stationary objects, sheaves are attached to the load you wish to lift or another sheave. Like the handle of the hammer, sheaves allow you to reduce the force needed to lift an object by applying that force over a greater distance.

Using only a single fixed pulley to lift a load, the force you apply to the rope is the same as the force you would use to lift the load without the pulley. Because the force doesn’t change, these systems don’t offer a mechanical advantage. Each section of rope that supports the load increases the mechanical advantage of the machine.

As you can see in the above diagram, the moveable pulley system has one rope section which supports the load. This one supporting rope section increases the mechanical advantage of the system. Because the pulley/sheave rotates, the rope moves 2x farther than the load but requires 2x less force to move.

The compound pulley system has two sections of rope supporting the load, providing an even greater mechanical advantage. By combining fixed and moveable pulley’s you can change the force needed to move an object and the direction in which the force is applied.

With both levers and pulleys, the total force needed to move the object a given distance never changes. The simple machines just allow you to apply that force over a greater distance.

Pulleys/Sheaves and Cranes

Cranes work by using pulley systems to change the direction of the force needed to lift a load and to distribute that force over a greater distance. At the far end of the boom rests the main boom tip sheave. Running through this sheave is the main load line, which has another sheave on the opposite end within the load block. This load block includes a hook that holds the load.

(point to tip of crane arm – the highest point – and label it “main boom tip sheave”. point to rope dangling from it and label it “main load line”. Point to the pulley in the middle of the main load line and label it “load block”)

The main load line is a steel cable that can only support a finite amount of weight. While that might seem like a lot, cranes often lift loads weighing hundreds of thousands of pounds. To prevent the cable from snapping under that force, cranes use pulleys to distribute the weight of the load over multiple sections of supporting cables.

If you look closely at the image above, you can see two sections of supporting cable running between the boom tip sheave and the load block. Each of the supporting sections increases the crane’s mechanical advantage, increasing the crane’s line pull, the total weight that the cables can support. Additionally, the sheaves allow the crane to apply less force over a greater distance to lift the load.

A crane’s boom acts as a lever, allowing the engine to apply a greater force over a shorter distance to lift the load. Additionally, it forces cranes to use counterweights that are heavier than the load to prevent the crane from tipping during lifts.

A steel cable connects the boom to the load via a series of sheaves. These sheaves help distribute the weight of the load over multiple supporting sections of cable, increasing the crane’s line pull.

Now that you know how cranes work, keep us in mind the next time you have a job that requires heavy lifting. La Grange Crane is one largest crane rental companies in the Midwest. We specialize in small crane rentals, but they’re only small in comparison to tower cranes. Our largest cranes reach hundreds of feet in the air and can lift loads weighing more than 500 tons.

If you’re interested in joining the industry, stop by our crane careers page. We’re always looking for inquisitive minds to join our growing team. Working with cranes is one of the most exciting career paths there is. Sure, we might be biased. But the sense of pride that comes from driving around the city and seeing the fruits of our labor is something we wouldn’t trade for the work